Executive Summary

As state and local jurisdictions seek to release more people from jail to await trial in the community under the least restrictive conditions, government stakeholders are questioning how to maximize the freedom of clients released without reproducing the harms of pretrial incarceration. In adopting changes to pretrial release policies, pretrial supervision agencies have faced larger caseloads and more judicial requests for burdensome and expensive requirements such as mandated client drug testing and electronic monitoring devices. Harris County, Texas is one example of a jurisdiction managing these implementation challenges, as it saw a 770% increase in the number of individuals on pretrial supervision since 2017. The Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab (GPL) helped the county test an approach to better manage this influx of clients by reducing the use of restrictive court conditions placed on clients released to the community pretrial. The pilot in Harris County sought to address and right-size that growing caseload by involving both pretrial staff and judges in reviewing condition placement within 30-120 days to adjust condition intensity and frequency. Through this pilot, from October 2020 to June 2022, the agency successfully adjusted supervision conditions for over 2,200 clients with no changes in client compliance or rearrest rates during that time.

A Snapshot of Harris County’s Pretrial Population

- Began enacting misdemeanor bail reform changes in 2018, increasing the share of defendants released pretrial on unsecured bonds

- Pretrial agency has one of the largest number of clients on supervision in the country (reached 30,000+ in 2021)

- Pretrial release conditions can include required in-person or remote check-ins, curfews, electronic monitoring devices, randomized drug tests, no drinking rules, no driving rules, exclusion zones,

- Judges or magistrates are responsible for choosing what pretrial conditions are required

- Pretrial agency and district attorney’s office can provide guidance to judges about condition recommendations, but judges have the ultimate say on condition placement

The Challenge

Harris County Pretrial Services (HCPS), like other supervision agencies nationally, provides court-ordered supervision to tens of thousands of people who are awaiting trial in the community. Since 2017, the agency has seen a 770% increase (from ~3,750 to ~32,500) in the number of individuals placed on supervision, and client to staff caseload ratios have exceeded 200:1. The intensity of supervision that clients receive can vary greatly, from monthly phone check-ins to randomized weekly in-person drug tests to constant electronic monitoring (i.e., through an ankle monitor). For each additional condition placed on an individual client, staff spend extra time monitoring, confirming compliance, and writing individual reports for judges while still conducting standard supervision check-in appointments with numerous other clients on their caseload. Under current policy, criminal court judges or magistrates are responsible for setting a client’s conditions of release, meaning HCPS has no control over how many people are placed on supervision, for how long, and under what conditions. As a result, HCPS has had more people on its caseload and on intensive supervision conditions than it has had the resources to effectively manage, with staff and clients bearing the brunt of the consequences. At the start of GPL technical assistance, criminal court judges in the county had not seen data on the total number of individuals on pretrial supervision or assigned to conditions in their courtroom. Judges wanted to address the strain of the supervision requirements on the agency and clients, but they did not feel they had the tools necessary to effectively right-size their use of conditions.

Potential Harms of Pretrial Supervision in Harris County

Overall, research on the effectiveness of pretrial supervision is limited. A review of studies on drug testing in cities across the country indicates no clear association between drug testing and a client’s likelihood of appearing in court or remaining arrest-free. These types of supervision requirements stretch the capacity of HCPS staff and are potentially harmful to pretrial clients in a number of ways, including:

- Accessibility and burden: HCPS serves all of Harris County, which is geographically larger than several states, with only one physical location. Many pretrial conditions require a client to come into the office on short notice, meaning that clients have to call out of work or find childcare coverage and incur the travel costs. Notoriously long wait times to meet with pretrial officers exacerbated this burden, and as the pandemic worsened, posed serious health risks. Given the overrepresentation of low-income and persons of color in Harris County’s justice system, this burden is especially felt by marginalized communities.

- Punitive consequences: While consequences vary, the court can jail clients for failing to comply with supervision conditions. This is a risk for clients facing challenges, such as transportation, childcare, employment, or housing, which make it difficult for them to meet their requirements. For example, clients called in for random drug testing risk going to jail if they cannot arrange transportation to HCPS with less than 24 hours’ notice.

- Fairness: Some judges impose general restrictions unrelated to an individual’s circumstances. For example, some clients are placed on a weekly drug testing condition even if their case is unrelated to substance use or are required to wear an ankle monitor even if their case has no restricted location. These requirements are particularly worrisome because pretrial clients have not been found guilty and by law are presumed innocent.

In addition to resource constraints brought on by high caseloads, the types of supervision conditions set by the court are often costly and overburdensome to pretrial clients, who have not been tried or convicted of a crime and who by law are presumed innocent. While pretrial supervision is designed to serve as an alternative to awaiting trial in jail, it can involve strict reporting requirements and financial costs that disrupt people’s lives and put them at risk of being incarcerated if they cannot comply. Once a condition is set by the court, there is no standardized system in place to remove it, and clients are usually stuck with the condition for however long it takes for the court to resolve their case. In some cases, defense counsel may raise a request for a condition amendment, but in those situations, clients are primarily reliant on their defense counsel taking individual initiative to do this. Throughout the GPL’s time in Harris County, more than 50% of cases were taking more than a year to be disposed, due to various compounding factors including Hurricane Harvey and the global COVID-19 pandemic. For example, if a judge ordered mandatory random drug testing and a client’s case took over one year to resolve, the client could be called in as often as once per week for testing over the course of the entire year.

The Innovation

With support from the GPL, HCPS piloted a new model of pretrial supervision that aimed to reduce the costs and harms associated with in-person check-ins, drug tests, and constant electronic monitoring for clients with a track record of compliance. The pilot project focused on equipping judges and HCPS staff with ongoing client compliance data that would enable them to monitor and adjust the intensity of these pretrial requirements through the course of a client’s supervision period.

“Pretrial agencies should be using the least restrictive conditions possible to supervise clients and step-downs are in line with legal and evidence-based practices (LEBP). This pilot demonstrated that people who had a step- down remained arrest-free at the same rate as the general pretrial population. Using a consistent and strategic approach toward step-downs was one of the first steps in moving towards LEBP for pretrial supervision at HCPS. We now want to expand on this pilot to support judicial decision-making to reduce unnecessary use of conditions placed on people earlier in the process.” — Natalie Michailides, Harris County Pretrial Services Director

Three key strategies guided the pilot program’s approach:

1. Establishing eligibility criteria for condition adjustments/step-downs

Project partners wanted to create opportunities for the court to update supervision requirements based on real-time information about client behavior. Previously, judges did not have consistent access to data about which clients in their courtrooms were compliant throughout their time on pretrial supervision. Through the pilot, the GPL tracked and elevated that information to judges on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. First, the GPL, HCPS leadership, and an initial set of six criminal court judges worked together to establish data-driven criteria for determining which clients would be eligible for a “step-down” in the intensity of their pretrial requirements. These step-down criteria provided pretrial stakeholders with standardized guidance for assessing how well a client was doing at an early stage in the supervision period. The pilot design originally included three types of step-downs that allowed pretrial agency staff to safely limit the number of costly in-person contacts taking place by either reducing the number of check-ins required, allowing for remote check-ins, or reducing the number of drug tests required.

2. Developing a standardized system for tracking client compliance in real-time

Prior to this pilot, if pretrial officers wanted to assess which clients on their caseload were compliant, they would need to sort through thousands of lines of narrative-form text case notes per client. If judges wanted similar information about who on their docket had been compliant with conditions, they would have to request this information per individual from either defense attorneys or pretrial officers. To implement the new step-down strategies, project partners needed a new way to automatically identify eligible clients without reading through thousands of case notes. The GPL designed a new standardized case note process that allows staff to continue to use narrative notes but also enter a quick, standardized code (i.e., “C” for compliant and “NC” for non-compliant) at the start of their case notes that allowed for easier identification of compliant clients. GPL staff created and delivered an interactive training for 112 pretrial officers and 10 supervisors across the agency to use this new compliance tracking system to make it simpler to flag clients consistently meeting their reporting requirements without creating additional strain on staff resources.

With GPL support, the pilot used this standardized case note process to analyze the compliance data entered by pretrial officers weekly to determine individuals eligible to receive a step-down. From this weekly analysis, participating judges receive an individualized list of clients in their courtroom who are eligible for reduced supervision requirements. Because judges in the county typically have more than 1,000 individuals on their dockets at any time, having a targeted list of clients to review allowed them to revisit conditions more quickly and regularly. Judges in the pilot have one week to review and deny a step-down if they have a concern. After one week, pretrial officers rereview and automatically step down the eligible clients that remained compliant. Given the large volume of cases judges and officers are managing, this default step-down process helps to avoid unnecessary delays.

Co-Designing the Step-Down Process with Court Judges and Doubling Judicial Participation

The GPL co-designed the step-down process with court judges. Judges weighed in on eligibility criteria and process details. For example, judges shared that they typically wanted to see 30-60 days of compliance before adjusting any conditions and wanted to use that as a starting point for the criteria. Judges also shared how often they wanted to review lists and what types of information they needed on the lists to make the process manageable for them.

This co-design ensured regular participation from the judges. By aligning on the initial criteria for a step-down upfront with judges, the GPL was then able to create an automatic step-down process to avoid delays. Working with the judges to co-create and implement these new processes was pivotal to pilot success and ultimately to alleviating the strain on the agency and pretrial clients.

Prior to the pilot, judges felt that they were not receiving regular useful data or information from HCPS. The pilot has created an improved communication pathway between pretrial officers and judges, working together to build a mechanism that better serves clients in supervision. Once judges were able to establish good communication with HCPS, they began to trust the process and recruit their peers to join the pilot. The pilot started with six court judges and over the course of the year more than doubled to 13 out of the 39 criminal court judges in Harris County.

3. Equipping judges with more representative data on client compliance

Judges in Harris County were looking for tools to understand how many people were being supervised, on what conditions, and with what levels of compliance. Typically, judges in the county receive individual information about clients in their courtrooms only when something has gone wrong, such as a missed court date, violation of supervision condition, or new arrest. This gives judges less exposure to how well an average client on pretrial supervision is doing while awaiting trial. Judges also shared that they were unaware that most individuals on supervision were compliant with their bond conditions because they only regularly received information about bond violations. To counter this, GPL staff created pilot data dashboards to track rates of compliance and rearrest for clients in pilot and non-pilot courtrooms.

“I had been interested in creating a more responsive supervision system for some time, but I did not have the information I needed to make condition adjustments. I saw that throughout the county cases were taking longer to be disposed and no one was talking about how to systematically get people off of supervision. I saw the step-downs pilot, and all the information that accompanied the pilot, as a proactive step towards shortening the time individuals were on conditions and making conditions less costly to clients. For these reasons, I joined the pilot and recruited my peers to do the same.” — Judge Sedrick Walker, Harris County Criminal Court at Law No. 11

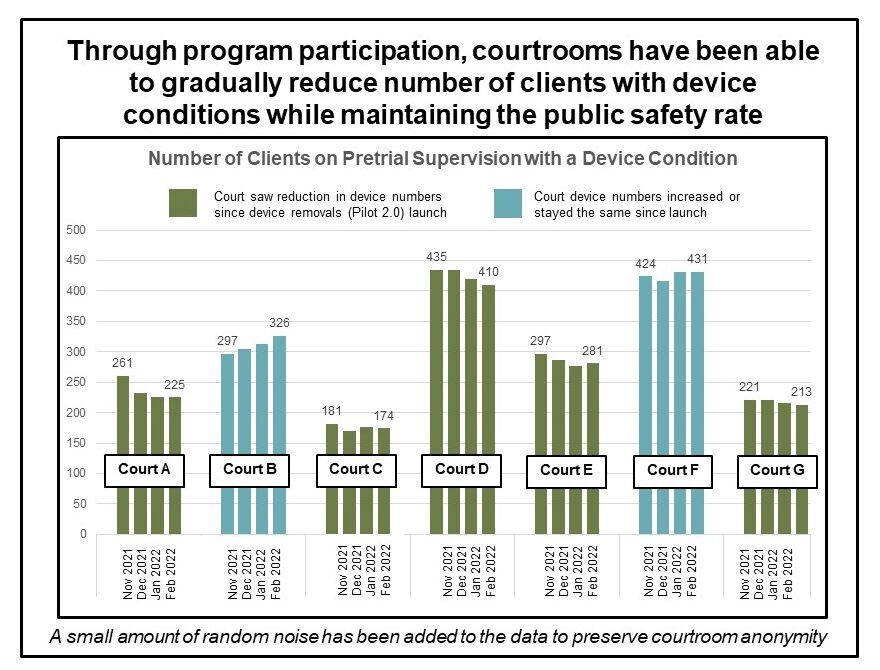

HCPS had also, due to resource and capacity constraints, been unable to give judges insight into how many conditions they were placing. This meant that judges did not have a sense of how common or appropriate their use of restrictive conditions was. For this reason, the GPL’s dashboards also showed judges for the first time how many total clients they had placed on various conditions and how that number compared to other peer courtrooms (see Figure 1). The GPL would share this data at quarterly meetings with participating pilot courtroom judges and HCPS staff. As part of the meeting, GPL staff invited judges to discuss their decision-making process in applying or adjusting supervision conditions and ask questions about the way supervision worked overall. Judges in the quarterly meetings had the opportunity to troubleshoot with their peers and request additional information specific for their courtrooms, opening lines of communication between pretrial stakeholders.

The Results

1. Stepped down 2,200 pretrial supervision clients with no changes in client compliance or rearrest rates during that time

The step-down supervision pilot was launched in October 2020 and through the first year, 2,253 condition adjustments were approved, benefiting 2,027 clients. Over time, judges became more comfortable with the practice of regularly reviewing and reducing conditions. Approximately 99% of proposed step-downs were approved by judges. Judges, the GPL, and HCPS began working together to look for ways to reduce unnecessary conditions. In particular, step-downs were effective but limited in that they removed conditions only after several months. Could similar data-driven approaches be used to reduce initial condition placement? Halfway through the first year of the pilot, several judges elected to participate in a one-time drug testing condition review of all the cases in their courtroom, 36% of which had the drug testing condition despite not having a drug related charge. This led to 701 clients having their randomized weekly drug testing conditions eliminated and a behavioral shift where judges began to reconsider when to place drug testing conditions.

After the first year of the pilot, the agency and judges also agreed to add a component for reviewing compliance and removing electronic and alcohol monitors—the most restrictive pretrial conditions. This resulted in bringing the total number of step-downs/condition adjustments to 2,546, benefiting 2,211 clients, at the end of GPL technical assistance (October 2020–June 2022).

Preliminary county arrest data indicate that there have been no corresponding changes in client compliance rates or rearrest rates during this period. This initial local safety rate data from a 12-month period showed that step-down clients had nearly identical rates of rearrest and condition compliance as the general pretrial population.* The safety rate for both the step-downs and general pretrial population remained constant even as the pilot grew to step down more people. The safety rate data also confirmed that the vast majority of people are not rearrested while on pretrial supervision in Harris County, which is in line with national trends.

These clients, who are by law presumed innocent, have benefited from increased liberty while on pretrial supervision, with fewer requirements to check in in-person and fewer random weekly drug tests.** Clients have shared that these shifts in requirements have reduced or eliminated the number of times they must leave work, find childcare and transportation resources, and travel across the county for in-person supervision meetings. Reducing supervision intensity also reduces the likelihood of technical violations that prolong criminal justice system exposure and decreases the costs born on both clients and agencies.

2. Reduced the administrative burden on pretrial supervision staff

As a result of making these changes to the supervision system, HCPS staff have fewer clients on their caseload with the highest intensity conditions, freeing up agency resources to focus on higher priority cases and creating increased capacity to implement additional innovative strategies.

“One of the biggest challenges we face is that my staff are overwhelmed with high caseloads that have many clients with resource-intensive conditions that last a long time. The pilot provided a better way to manage their caseloads. The new compliance case note system, initiated by the pilot, helped staff quickly track client progress and work with judges to adjust conditions, allowing my staff to focus on their highest-risk cases.” — Janey Smith, Harris County Pretrial Services Court Support and enhanced Supervision Division Supervisor

Piloting these step-down strategies also helped build stakeholder support for long-term improvements to supervision practices. For example, building on strategies discussed in the pilot planning phase, HCPS adopted a default remote check-in policy for all clients except those with the highest level of supervision requirements.

If scaled across all court rooms, these strategies have the ability to further reduce office crowding, decrease personnel and monetary costs associated with administering drug tests, and allow staff to reallocate time to the highest-need cases. GPL staff are now applying the learnings of the step-down pilot to support HCPS in rolling out an agency-wide policy to allow for regular removal of device conditions for clients with demonstrated compliance.

FOOTNOTES

*It is not clear a priori whether we should expect step-down clients to have similar rearrest rates as the general pretrial population. On the one hand, the population approved for step-downs could include individuals with a higher likelihood of rearrest than the general pretrial population because to be eligible for a step-down, individuals had to have a sufficient number of supervision conditions placed on them. On the other hand, compliance with conditions may imply a lower probability of rearrest, and judges may have chosen to approve lower risk clients for step-downs more often.

**The random drug testing requirement can be particularly onerous for clients. Clients required to participate must log in to an application every morning to see if they have been randomly selected for a drug test. If selected, clients often must give last minute notice to work, find childcare, and spend their day traveling downtown to stand in line and meet with an HCPS employee to submit a urine sample.

More Research & Insights

Measuring Pretrial Success: Two Scenarios for Agencies and Courts

GPL Presents on its Work with Judges in Harris County, Texas to Reduce Pretrial Condition Use

GPL Presents on the Use of Service Referrals During Pretrial Release in Alameda County, California

Measuring Pretrial Success: Two Scenarios for Agencies and Courts