Strengthening Alternative 911 Emergency Response

Nationally, a growing number of jurisdictions are launching alternative 911 emergency response initiatives. The goals of these programs are to help more individuals in crisis get the right kind of help at the right time, reduce overreliance on law enforcement, and free up the capacity of traditional first responders to focus on pressing public safety concerns and medical emergencies. In many alternative response programs, unarmed teams staffed by social workers and other trained specialists are dispatched to certain emergency calls, such as those related to mental and behavioral health.

Over the past three years, the Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab (GPL) has worked with more than 30 jurisdictions to develop, improve, and expand these programs through its Alternative 911 Emergency Response Implementation Cohort. Through this applied research support and technical assistance, the GPL helps jurisdictions navigate a range of questions related to implementing alternative 911 emergency response services. Common questions include:

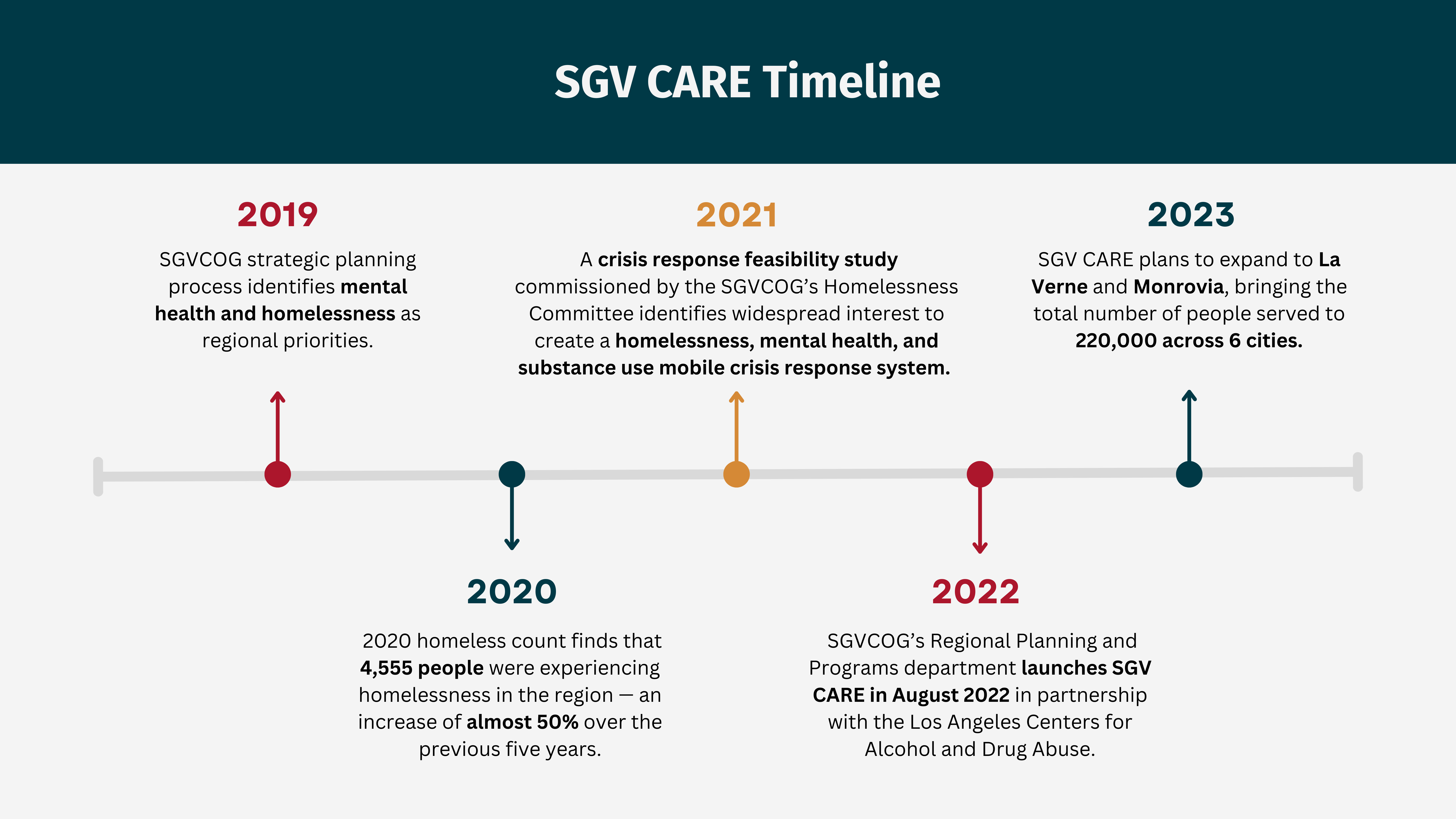

Since 2021, the GPL has worked with the San Gabriel Valley Council of Governments (SGVCOG), to launch an alternative emergency response program. The SGVCOG is a regional government planning agency in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles County. It consists of 31 incorporated cities and encompasses more than 374 square miles and 2 million people.

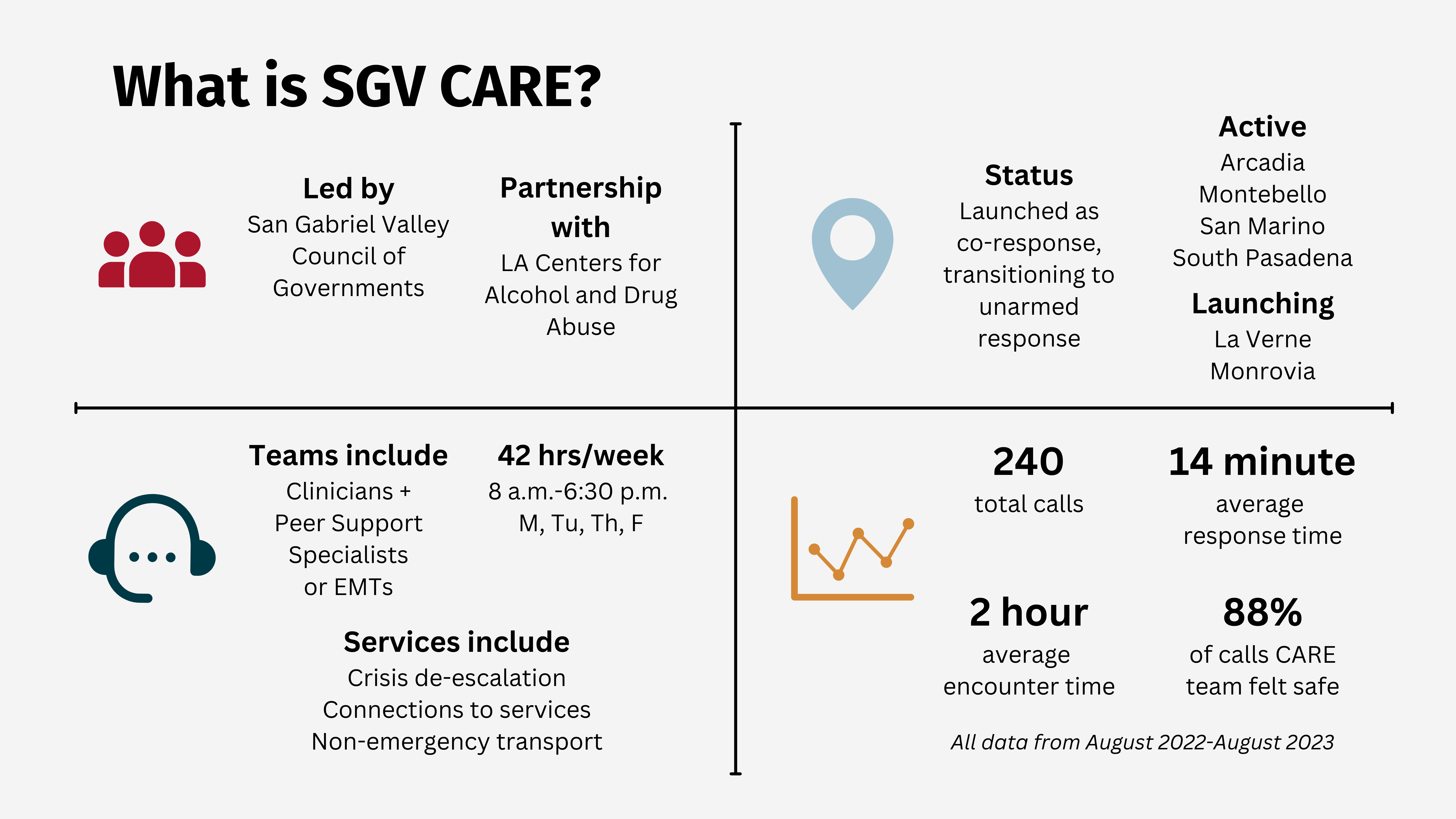

The SGVCOG’s alternative response program, San Gabriel Valley Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement (SGV CARE), is unusual in its structure as a multi-city initiative. This regional approach allows a group of smaller cities, which would otherwise not have the capacity and resources necessary to operate their own programs, to launch alternative emergency response services at no cost to the participating jurisdictions.

SGV CARE includes two mobile crisis response teams: one serving the Cities of Arcadia, San Marino, and South Pasadena, and another serving the City of Montebello. Two additional cities, La Verne and Monrovia, are now being onboarded to the program. After this expansion, SGV CARE will serve six cities encompassing more than 220,000 people.

The program currently uses a co-response model, in which teams are deployed alongside police officers, with plans to transition to an unarmed alternative response model. From August 2022 to August 2023, the SGV CARE team received 240 calls, most of which were related to a person in distress or mental health.

SGV CARE was initially launched using Measure H funding, a sales tax for homelessness programs in Los Angeles County. Through government relations and lobbying efforts, the SGVCOG also received $850,000 in state funding and $1.5 million in federal funding. These financial resources will sustain the program through early 2025 and allow the SGVCOG to provide SGV CARE at no cost to participating jurisdictions.

As jurisdictions across the country reimagine their approaches to public safety, SGV CARE’s early experience provides valuable insights into what it takes to develop and implement a multi-jurisdiction alternative 911 emergency response program. These insights also offer broader lessons relevant to any jurisdiction interested in alternative response.

The GPL interviewed Sam Pedersen, management analyst at the SGVCOG and lead program manager for SGV CARE; Lieutenant Tony Juarez from the Arcadia Police Department; and Yvonne Duran, community services director for the City of La Verne, about key insights from initial implementation of SGV CARE. These leaders highlighted three key lessons for implementing alternative 911 emergency response programs:

Each lesson also includes specific takeaways for programs operating across multiple jurisdictions. Those are highlighted below in boxes titled “Multi-jurisdiction consideration.”

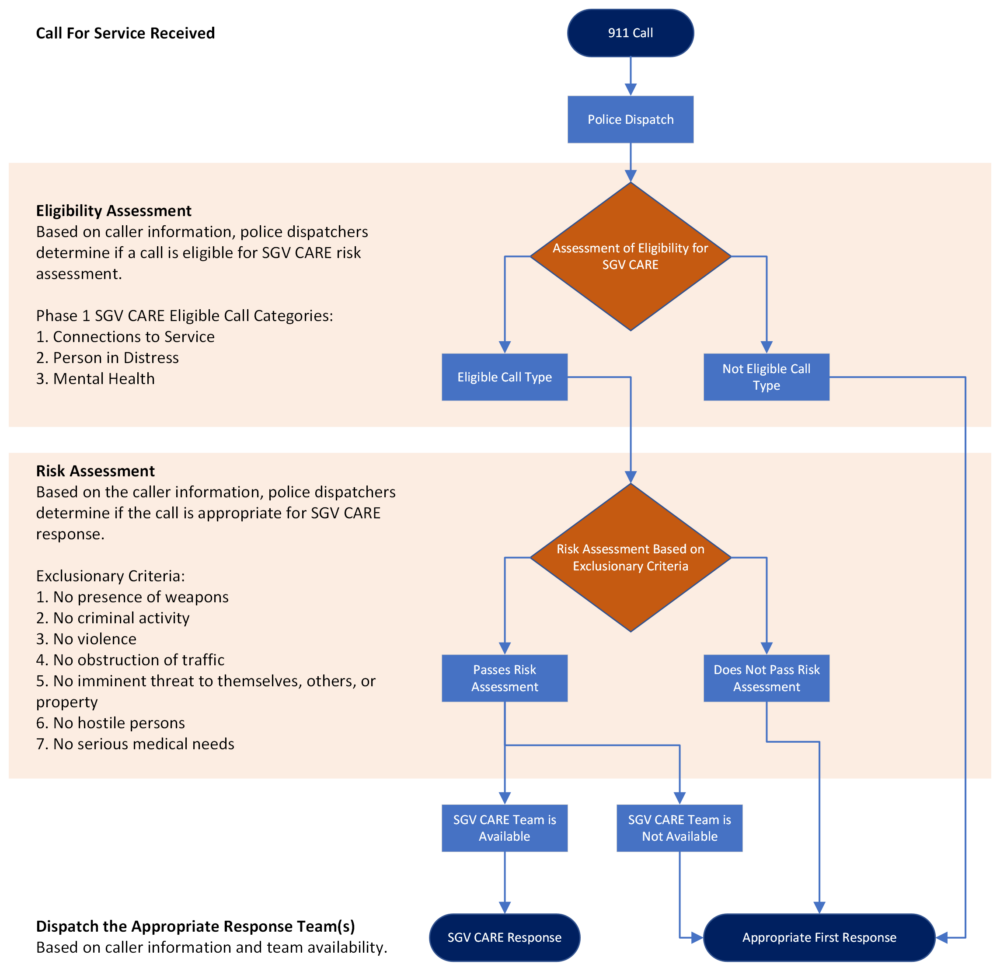

Determining which types of emergency calls are safe and suitable for an unarmed emergency response team is a crucial decision during the program planning phase. For example, calls related to mental and behavioral health, quality of life, and homelessness might be identified as suitable for an unarmed emergency response team, whereas calls related to property crime may not be.

Jurisdictions often develop exclusionary criteria to ensure calls that pose a safety risk do not receive an alternative response, even if they fall into an eligible call code category. In Harris County, Texas, for example, an indication of intent to use weapons or violence during a 911 call leads to automatic exclusion from alternative response.

To begin the process of identifying eligible call codes in the San Gabriel Valley, the GPL and the SGVCOG convened representatives from participating cities for a six-meeting sprint in December 2022 and January 2023. The GPL guided participants through call scenario generation exercises to discuss a variety of possible 911 call scenarios and determine which would be appropriate for a response from SGV CARE.

“They [the SGVCOG] held several sessions with a lot of great questions on the SGVCOG’s end in determining how we filter calls for service. We had dispatchers, myself, and sergeants present for all these sessions to brainstorm what we felt was OK for the team to respond to.” — Lieutenant Tony Juarez, Arcadia Police Department

Using findings from these discussions, Pedersen and representatives from the participating cities selected three eligible call categories to begin piloting: connections to services, person in distress, and mental health. If a 911 call falls within one of those categories, a dispatcher assesses whether it is safe for the SGV CARE team to respond. The dispatcher uses exclusionary criteria such as the presence of weapons, criminal activity, violence, or serious medical needs.*

Oftentimes, 911 call codes do not match across jurisdictions, which can complicate the selection process for eligible calls. For instance, a 911 call related to a mental health crisis may be recorded as a different string of letters or numbers among different cities.

“Each city has its own unique way of call coding. When we’re starting off with a cohort of three cities … getting those three cities to even speak the same language was a hurdle.” — Sam Pedersen, lead program manager for SGV CARE

To remedy these differences, the GPL and the SGVCOG held sessions where cities first identified appropriate call scenarios for alternative response, such as suicidal ideation. After building roughly 50 of these scenarios, 911 dispatchers from each city were asked to identify how they would code those scenarios. The SGV CARE program protocols are city-specific to ensure unique call codes are captured for each city.

Jurisdictions may also use different and incompatible emergency computer-aided dispatch (CAD) and communication systems. In the San Gabriel Valley, this resulted in the SGV CARE team being dispatched via cell phone.

As the staff members responsible for triaging calls to alternative emergency responders, 911 call-center dispatchers are fundamental to successful implementation. Although Pedersen’s primary contact in participating cities is usually a representative from the police department (e.g., lieutenants or commanders) or the fire department, dispatchers played an important role in the design of SGV CARE.

Representatives from Arcadia and La Verne both emphasized how important it was to involve dispatchers in early conversations about the program to gain their buy-in and unique insights, particularly regarding the selection of appropriate call codes. Dispatchers were invited to join the call scenario generation exercises to lend their perspectives.

“Sometimes they [dispatchers] couldn’t make a meeting, and we would switch meetings to make sure they were there. We wanted their buy-in, and we wanted them involved, so we made those accommodations throughout this process.” — Yvonne Duran, Community Services Director for the City of La Verne

The SGVCOG also provided training to dispatchers on how to implement the dispatching process. With support from the Arcadia Police Department, the SGVCOG developed, coordinated, and conducted a one- hour training for all 911 dispatchers. This included an overview of SGV CARE, a program success story, details on the dispatching process, communication procedures, and scenario role playing.

With participating cities experiencing dispatcher shortages, Pedersen prioritized flexibility. For instance, he led one-on-one trainings during his usual off hours to accommodate dispatchers’ schedules. The individualized sessions created space to directly address dispatchers’ questions and concerns. Dispatchers then had two weeks to practice using the new protocols prior to program launch. For the first two weeks after SGV CARE went live, dispatchers checked in with their supervisors daily. By prioritizing a high degree of dispatcher training and engagement, dispatchers were better positioned to accurately screen and triage 911 calls for SGV CARE services from the start.

“With dispatch, people don’t realize how much they have to multitask during their shift. It was crucial to bring them aboard on this. We might not see something that they see based on how they receive calls. They had a lot of great points and a lot of great questions on this process.” — Lieutenant Tony Juarez, Arcadia Police Department

The cities participating in SGV CARE have different triage procedures for 911 dispatchers. This impacts the type of information they collect from callers and in what order, as well as how they triage calls to different response services, such as police, fire, or animal control. To address these discrepancies, Pedersen customized dispatching protocols and training based on a dispatcher’s jurisdiction and corresponding triage protocols, rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach.

Analyzing data is crucial to understanding how alternative emergency response services are performing and then communicating their impact to key stakeholders, such as the police department and the public. Pedersen started by considering what performance metrics the SGVCOG could plausibly track, which ones were most valuable, and how frequently they would be collected.

One metric the SGVCOG tracks is the SGV CARE team’s perceptions of safety while responding to calls. This metric — which is also tracked in other Alternative 911 Emergency Response Implementation Cohort jurisdictions, like Durham, NC — allows the SGVCOG to identify if the SGV CARE team feels safer responding to certain types of calls. Other types of data the SGVCOG tracks include response time, encounter time, data on follow-up visits with clients from previous calls, and data on the types of services provided by the SGV CARE team. Summary reports are shared with participating cities weekly via email to provide regular updates on the program’s status and to inform operational improvements. The SGVCOG also shares monthly reports that pair data insights with personal narratives.

“I think programs like this can get lost in numbers. Storytelling is really important in a program like this, so we always include a case review or program success story highlighting how the team was able to help a resident.” — Sam Pedersen, lead program manager for SGV CARE

Given the urgency of behavioral and mental health needs in the community, SGV CARE launched as a co-response program where teams respond to calls simultaneously with law enforcement. The data that the SGVCOG collects is now being leveraged to showcase the progress of the program, build trust with key stakeholders, and help facilitate its transition to unarmed response, at which point SGV CARE teams will respond to calls independent of law enforcement.

An alternative 911 emergency response program operating across multiple jurisdictions may contract with more than one service provider. Although the SGVCOG only contracted with one, LA Centers for Alcohol and Drug Abuse (LA CADA), Pedersen emphasized the importance of ensuring that all providers can deliver information in a consistent, usable format, such as data that is already de-identified. This data can be used to better understand the program’s impact and to assess how vendors are performing.

Alternative 911 emergency response programs seek to transform how communities deliver emergency services. This creates common technical challenges — such as selecting the appropriate call codes and tracking data — as well as challenges related to collaborating with numerous stakeholders. Police departments, fire departments, EMTs, 911 dispatchers, elected officials, social services agencies, mental health clinicians, and residents are often closely involved in the development and implementation of these programs.

As SGV CARE continues to expand, leaders in the San Gabriel Valley see a future where community members experiencing mental and behavioral health crises are better connected to the services they need while reducing the burden on law enforcement. SGV CARE is currently working on expanding services in La Verne and Monrovia, securing additional funding for future expansion, and partnering with an external research organization to review the program’s performance.

“What I hope other cities see is that alternative response is an instrumental service to have for your community. Not everybody responds well to officers; not everyone wants to see a person in uniform. Sometimes, people just want someone that’s in regular clothes when they’re having a bad day.” — Yvonne Duran, community services director for the City of La Verne

Ultimately, Pedersen recognizes that the alternative response program in the San Gabriel Valley can continue to test, grow, and improve — while still delivering crucial services to residents today.

“It’s important not to get stuck in trying to be the perfect mobile crisis program, because it doesn’t exist. Every single program, every single jurisdiction is really very different. This is a needed service; this is an impactful service; it’s a powerful service. I think it’s more important to get mental health clinicians out there than to get stuck building out the perfect program.” — Sam Pedersen, lead program manager for SGV CARE

For governments exploring, planning, implementing, or expanding alternative 911 emergency response teams, sign up for the GPL’s Alternative 911 Emergency Response Community of Practice. Designed exclusively for government staff, the community of practice provides representatives from over 80 governments across the country with practical tools and actionable insights emerging from the GPL’s alternative 911 emergency response work and research. The community of practice convenes monthly, providing a space for participants to engage with government peers on topics like stakeholder collaboration, community outreach, outcomes tracking, and more.

Strengthening Alternative 911 Emergency Response

Strengthening Alternative 911 Emergency Response

Strengthening Alternative 911 Emergency Response

Strengthening Alternative 911 Emergency Response

Strengthening Alternative 911 Emergency Response

Strengthening Alternative 911 Emergency Response